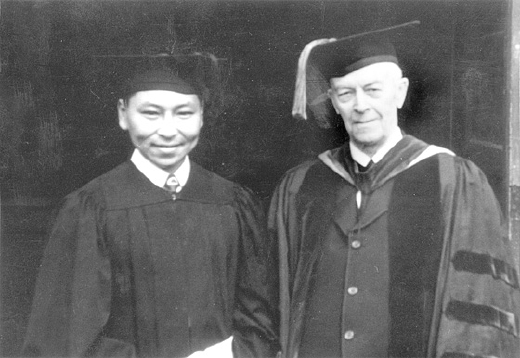

Arthur Nagozruk Jr.

Arthur Nagozruk Jr. was the University of Alaska’s first Inupiaq graduate, but he was no stranger to education — his father was Alaska’s first Inupiaq school teacher. Nagozruk Jr. himself followed that path after graduation before turning his efforts toward organizing tribal governments as a federal Bureau of Indian Affairs officer in Nome.

Nagozruk Jr. was born May 10, 1920, in Wales, the village on the westernmost point of mainland Alaska, according to his daughter, Sharon McClintock of Anchorage.

Nagozruk Jr. was the son of Lucy and Arthur Nagozruk Sr. Nagozruk Sr. lost his parents when he was young, so he was raised by his aunt and the missionary Lopp family in Wales, McClintock said. An academic prodigy, Nagozruk Sr. began teaching at 17 in the Wales school.

The 1918 flu epidemic killed many of the adults in the village, including Nagozruk’s first wife and two children. He was left with one daughter. He then married Lucy Alvanna, who had lost her husband and son, and they cared for survivors.

“Within weeks, he wrote 167 death certificates,” McClintock said. “Most victims were elderly and middle-aged. “It erased so much of the history of the people.”

Nagozruk Sr. taught in schools around western Alaska, and his growing family followed him. “My father got a great education not only in Inupiaq but also in Yupik and Cup’ik,” McClintock said.

At age 13, Nagozruk Jr. was sent to the BIA boarding school in Eklutna, just north of Anchorage. “He didn’t see his parents again until he was 31 years old,” McClintock said.

Upon graduation in 1937, the Army drafted him, and he served in the Aleutian Islands after the Japanese invaded. After his release, he enrolled at UA and earned a bachelor’s in education.

Nagozruk Jr. began his own teaching career in the coastal village of Wainwright, where he met and married Florence Ahlalook. They soon moved to Elephant Point, named for the mastodon tusks eroding from the village spit in Kotzebue Sound. Nagozruk Jr. helped his brother-in-law, the UAF-trained anthropologist Charles Lucier ’49, investigate artifacts in the Elephant Point area.

The erosion forced villagers to move 30 miles to Buckland, a resettlement that Arthur and Florence Nagozruk helped organize. Their children were born in Buckland.

McClintock, born in 1952, said her father taught in several villages before settling in Nome in 1960 to be near family.

In Nome, her father went to work for the BIA as a tribal operations officer. He helped tribal governments organize, wrote a book on parliamentary procedure for them and created constitutions. He also helped Native people with applications for individual land allotments before the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act passed in 1971. He would bring home copies of draft bills from congressional work on the land claims, which sparked McClintock’s lifelong interest in the subject. She and her husband own a surveying and mapping company in Anchorage.

Nagozruk Jr. died in 1976, at age 56. His wife, Florence, died in Anchorage in 2015 at age 89.

McClintock said she still hopes to publish a book titled “The Siberian” that her father wrote shortly after moving to Nome. It describes the life of the people of Wales and a Siberian man who elected to remain in Wales after Stalin created the Iron Curtain.

“He was a gifted writer,” McClintock said.

More online about Arthur Nagozruk Jr.:

- A 1981 profile of his father in the Northland News, a monthly Fairbanks Daily News-Miner publication distributed across northern Alaska

- An obituary for his wife, Florence

- Part one of a short story (PDF) he wrote, published by the Tundra Times in 1990