Flora Jane Harper

When Flora was eight, in the spring of 1918 the Spanish flu had reached Alaska and

was sweeping through the villages killing many. At this time Flora's father, Sam,

decided it would be safer for the family if they uprooted and moved to Nenana. Nenana

had a doctor, hospital and school. Here the family of six, with one on the way, lived

in a rented one room cabin about 10 by 14 feet with a wood stove. After their arrival

the entire family came down with the flu. With everyone too weak to even walk, Flora

gathered her energy to go out and get water.

She was found on the ground by a man named Francis near the town well as she attempted to get water for the family. He brought her back to the cabin and began to care for and nurture the entire family back to health. After the family slowly started to recover, Francis found a midwife for Louise Harper. She gave birth to a son and named him Francis Harper.

The transition to life in Nenana was difficult for the Harper family. Switching from the village life to a cash economy left them in poverty. The family continued to grow bigger and so did their poverty. Sam felt increasing pressure to do something about his situation as working for the railroad wasn't enough money for seven and counting.

Flora Jane was 10 years old in 1920 when she was sent to the Chemawa Indian boarding

school near Salem, Oregon along with her sister Elsie (age 8) and her brothers Arthur

(age 6) and John (age 4). Sam decided to send the four oldest children. All he had

to do was pay for transportation, clothes, and a few assorted school event expenses.

During her years at Chemawa, no money came to Flora and her siblings from the family,

so during the summers instead of traveling back to Alaska to visit, the children worked

at odd jobs. Upon reaching the tenth grade, Flora Jane was living with and working

for a doctor and his family. She and her sister Elsie then decided to stay in Oregon

and attend Grant High School in Portland. After high school, she contracted tuberculosis

and was hospitalized for nearly a year.

In 1929, because of the Depression, boarding schools across the country were closing their doors. The four Harper children had no choice but to return to Alaska after being separated from their parents for nine years. In their absence, Flora's parents had moved with the family from Nenana to Fairbanks and upon joining them visually realized that the family had grown considerably. The children who had been sent off to school had been replaced. There was now a total of 10 children. The house was crowded.

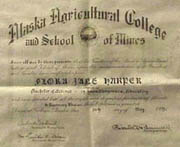

In 1931 following the role models of her elders, such as Walter Harper*, who was the first man to summit Mount Denali in 1913, Flora (Jane) Harper decided to enroll at the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines. After Jane’s father's unexpected death, life became more difficult for the Harper family. But Jane persevered and through the supportive faculty—President Bunnell, the Gassers and Lola Tilly— she became, at the age of 25, the first Alaska Native to graduate from the college. She received a bachelor's degree in home economics in 1935. Even after graduation, President Bunnell continued to have written correspondence with Flora Jane.

There is a wonderful set of photos taken by a Dr. Ticky in 1938 demonstrating Flora’s work with her young students. The children appear to be in their early teens and it gives a snapshot out of time in the history of Alaska Native education where young children were taken to large boarding schools and gone from their homes for long periods of time. Jane served as an inspiration to these young children as well as proving a friendly haven in a foreign place.

It is in Wrangell where she met and married Walter (Pete) Petri, a carpenter. They were married in the Episcopal Church in Wrangell on November 17, 1941. A year later the couple moved to Sitka, where Jane accepted a position teaching at Mount Edgecumbe school. In February of 1943 Flora gave birth to a daughter, Janet Frances Petri.

During the next few years, Jane taught at the following major Indian Boarding schools: Chiloco, Eklutna, Wrangell and Mount Edgecumbe. The impact of having an Alaska Native teacher on the Indian and Eskimo children attending these schools must have been just as significant then as it is today. The new term “Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK)” describes the pedagogic methods Jane brought to classrooms where she incorporated her Native knowledge into western classrooms.

In a personal effort to help out other struggling Native students attending the University of Alaska, Flora would send checks to the Office of Rural Student Services. Clara Johnson, the director of the Interior-Aleutians Campus, remembers fondly how they would distribute money from the "Emergency Fund” that was set up when they started receiving Flora's financial gifts. "We always tried to select a young Native woman who needed the extra cash to help make their life at the university a bit easier", said Clara. "It was a generous and welcome gift; Jane didn't want anybody to have to struggle to get an education the way she had. Remember, she was not a wealthy woman, she was just committed to helping others." In 1949, she moved to Anchorage and worked at the Loussac Library until her retirement in 1972. She died in 1992. In 1994 the University of Alaska Fairbanks named the Harper Building after her.

UA Site named after Flora Jane Harper

Sources:

Cold River Spirits: The Legacy of an Athabascan-Irish family from Alaska's Yukon River, Jan Harper Haines, 2000

Other facts

Flora Harper's uncle, Walter Harper, had been the first man to the summit of Denali in 1913. He had lead Archdeacon Stuck's climbing party. An article about his climb can be read here. Walter and his new bride, Frances Wells, later died in the sinking of the Princess Sophia.

Her brother, Francis Harper, was captured and imprisoned in a German POW camp. He was liberated in the spring of 1945.

1935 was the last graduating class of the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines, as the name was then changed to the University of Alaska. Article can be read here.