Understanding how wild harvests are impacted by environmental stress and the resilience of rural communities in Alaska

November 26, 2025

|

|

Davin Holen is a co-principle investigator on the Alaska EPSCoR Interface of Change project, co-leading human dimensions research on health and social, cultural, and economic well-being in rural coastal communities in the Gulf of Alaska. He is also the Coastal Community Resilience Specialist for the Alaska Sea Grant Marine Advisory Program. Across various projects, Davin facilitates workshops and other activities by building trusted collaborations to provide data and decision support tools to Alaskans to adapt to climate and environmental changes and build resilience and better community well-being. Before joining Alaska Sea Grant, Davin spent 15 years at the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, conducting social science research and managing the subsistence program in Southern Alaska. Davin is a lifelong Alaskan, growing up in Anchorage and the Susitna Valley, and he continues to split his time between his home in Anchorage and cabin in Talkeetna. |

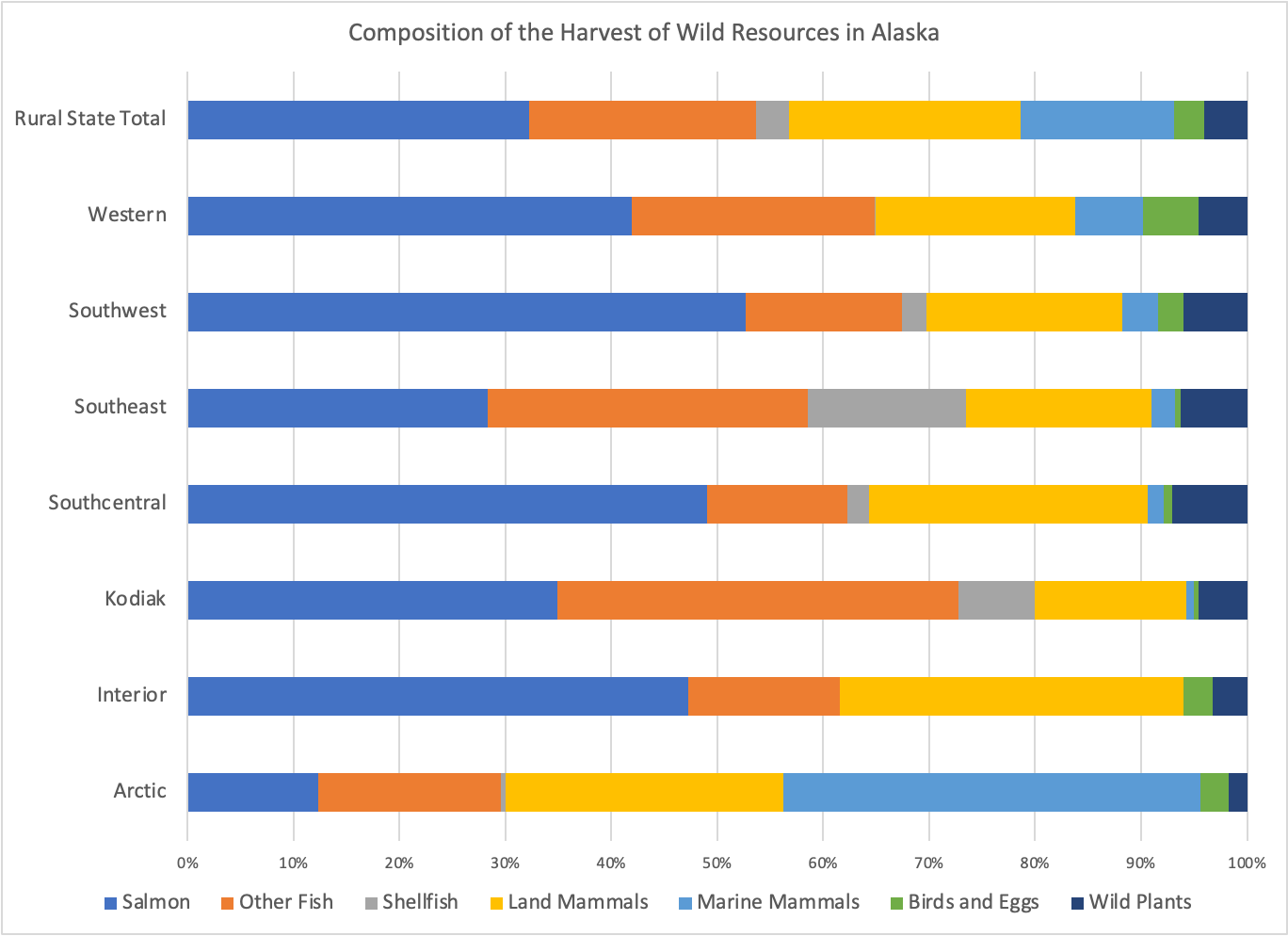

For over 40 years, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) Division of Subsistence, has produced annual harvest assessments based on voluntary, confidential household surveys that document the subsistence way of life in rural communities across Alaska. These assessments provide numerical and qualitative data at the community level on annual harvests as well as the variety of ways that Alaskans live a subsistence way of life. In aggregation, this dataset produced by ADF&G is one of the best longitudinal datasets on wild harvests at a community level in the North. Having spent 15 years of my early career administering surveys in households across Alaska from the Arctic to Southeast, I learned that the data tells the story that there is not just one subsistence way of life in Alaska. There are many, as each region of Alaska and community is unique (see figure below).

Between the NOAA Alaska Fisheries Science Center, Alaska Sea Grant, the Alaska EPSCoR Interface of Change project, and soon the NOAA Ocean Acidification Program, my collaborators and I use the publicly available data from the ADF&G Community Subsistence Information System to look for trends in harvest that might demonstrate how environmental stressors such as warming waters, ocean acidification, and fluctuating glacial runoff might be impacting a way of life in coastal Alaska.

But beyond the data, we want to know how these patterns really affect both subsistence harvesters and commercial fishers, and juxtapose what we find in our data analyses with human observations of change.

People make observations about things that are important to them all the time. While out fishing, hunting, or foraging, people are very perceptive to changes in the environment. They notice that the waters are warmer, that fish species are changing, and that their distributions are different. They see differences in abundance.

In southeast Alaska, in the communities where we're working, people have noticed that hooligan, an important resource with deep and profound cultural importance for the Tlingit people, are not coming as far up the river as they used to. They've noticed changes in the Chilkat River.

Everyone makes observations. Personally, I’ve fished in the Kasilof River every year for the last 20 years, standing in the same spot in the river every single year. Some years are better than others. I've noticed changes in water temperature, how they influence the number of fish actually in the river. How fast will I catch fish? Am I going to have to stay one tide? Two tides? A couple of days? Might I have to come back? Has it been raining? If there's not enough cold water in the river system, the salmon won't go up, they wait for that oxygen-rich cold water. You notice all these fluctuations. And then there's other things like: when are the commercial fishermen out? I don't fish right after a set net opening, because there won't be any fish – they've already been caught. Over 20 years of doing this, I’ve made these observations, and I pass these observations on to my son.

Now, if you think about a household that has been fishing in the same place for generations, passing that knowledge along – that's what's most fascinating to me.

I’m just one individual making observations, but a whole family line or entire community that have been making observations for generations – they've seen changes over long periods of time and transmitted their observations of those changes over time through their household, through their community, to the younger generation. And that’s how people build resilience. Because they recognize changes, they know what to look for, and they've made adjustments and adaptations over that period of time, and they've taught the younger generation how to do that.

So, this is why we value and respect the observations that people make in their environment and in their harvests, and why hearing directly from people is a critical part of our process.

After analyzing ADF&G harvest assessment data, we use the results from our analysis as a discussion point for people to respond with what they’ve noticed. For example: both harvest data and data available from biologists and resource managers suggest a decline in Chinook salmon. What does that mean to you?

We do this in groups. We organize groups of individuals to participate that each represent different backgrounds in the community. We facilitate a discussion where people bounce ideas off each other and compare what they’ve seen independently. Over multiple group interviews, we often begin to hear recurring themes. When we hear similar observations from many different kinds of people, this gives us what we call a “consensus analysis.” Consensus analysis provides both a solid data point and a place from which people can begin to make collective decisions around strategies for adaptation.

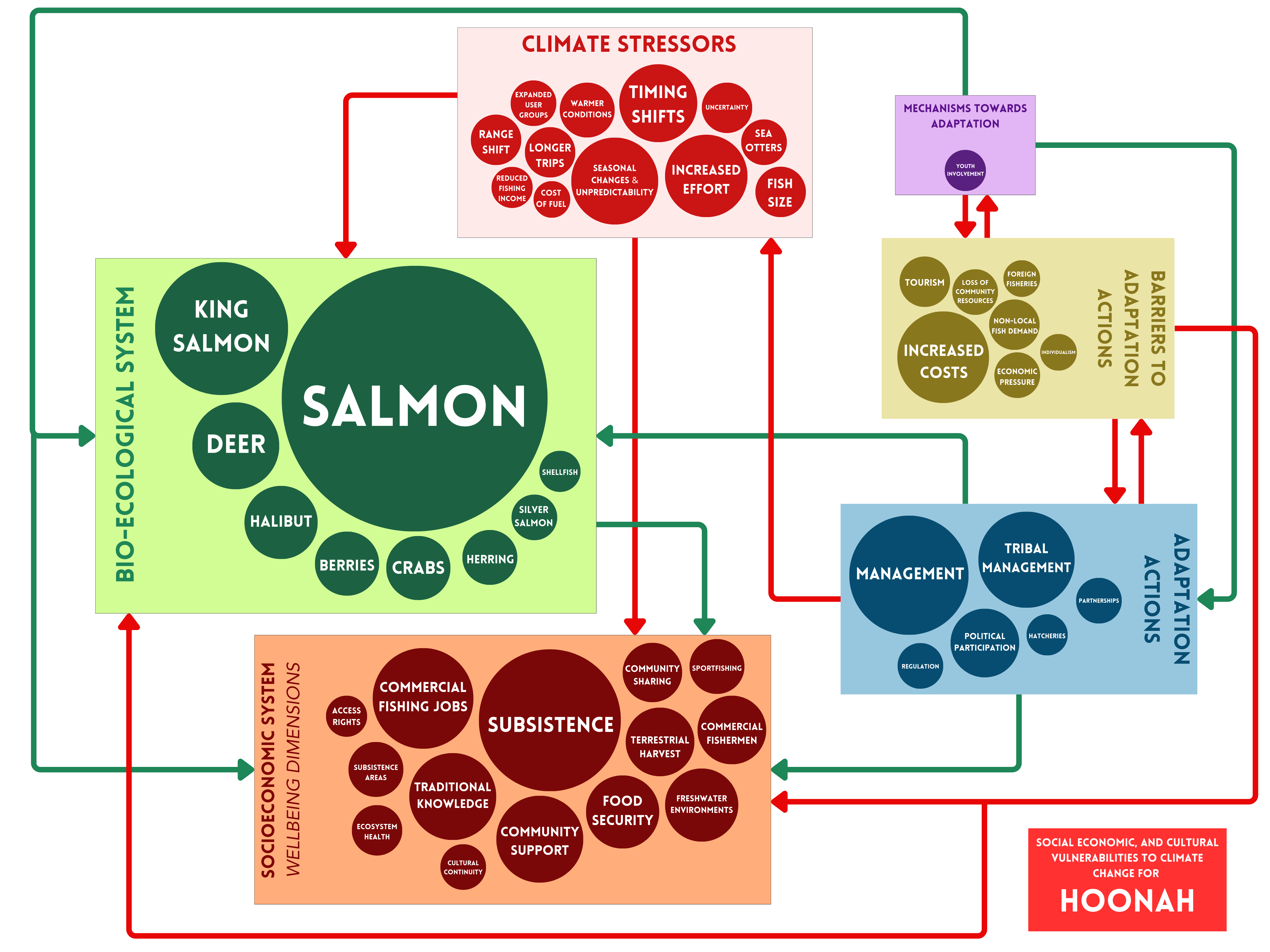

In the process, we visualize the overarching ecological and social and cultural drivers affecting harvests as a diagram to clarify the context around the changes people are observing. Through hosting workshops and diagramming systems, our team provides a platform for communities to tell their stories of why these systems, resources, and ways of life are meaningful to them, and reveal the ways in which communities are resilient and adaptive.

The question I continue to ask in my work is, ‘how do I create methods and data products that get into the hands of folks and are actually useful? And why should people care?’

Ultimately, our goal is to produce data and products that foster resilience and adaptation planning at the community level. By working with our community partners in a group setting, we can assist in creating a community conversation and getting a consensus on how to adapt to changes to come.

The word resilience can have a lot of different meanings for different people. But overall, I think of it as the ability to bounce back quickly, of learning to live with change.

For local harvesters, the actual act of harvest does not change, even if the world around us changes. Our connection to the land, our connection to the water – that’s what's important, however that connection is made, through whichever species we're harvesting. But in facing changes in the environment or in populations, how or what we harvest may need to change in order for us to adapt. People will continue to be tied to the lands and waters, and by actively engaging in harvesting resources, they continue the longstanding cultural traditions of their families.

Coastal communities in Alaska endure and learn to live through astounding changes. People learn to live with changing ocean conditions, weather, and other factors that affect their way of life in coastal Alaska. As a coastal community resilience specialist and an anthropologist who has spent a career researching the impacts of environmental change and technological disasters to ways of life across Alaska, my role is to make information available to help people understand the things they need to do if they're going to stay in the places they are tied to and learn to live with these challenges so that the next time a storm comes or a harvest is less abundant, people are prepared and they persist.